Women between war and peace

Date: 20 October 2016

UN Women originally presented these images from the archive of renowned photography agency Magnum Photos at the launch of the Global Study on the Implementation of Security Council resolution 1325 in 2015, to mark the 15th anniversary of UN Security Council resolution 1325 (2000), which recognized the critical importance of women’s participation in peacemaking and peacebuilding.

Women experience war differently from men. They see firsthand the unique impact that conflict, increased militarization and violent extremism has on their communities, their families, and their own bodies. Less visible than the headlines, however, is how women carry on in spite of violence that may surround them: they seek education, continue careers, and raise families — sometimes traveling long distances to bring their children to safety. They are also working to prevent conflict and extremism, and work as activists, judges, and government officials.

In the words of peace activist Sanam Anderlini, “wherever war and violence exist, women exist — and they have things to tell us.” As the United Nations and the world continue to seek solutions to global security crises and strive to build sustainable peace, it is our hope that these images serve as a reminder of the many ways women are working to prevent conflict and secure a sustainable peace.

NIGERIA. Lagos. 2006. Dora Akunyili, Director of the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control, stands in the charred remains of her former office, torched by arsonists in 2004. In 2003 she survived an assassination attempt by gunmen with AK-47s. Today, the insurgent group Boko Haram has killed civilians, abducted women and girls, and destroyed homes and schools. In countering the rise of violent extremism, women’s participation helps: they are often the first to identify signs of radicalization and act to intervene.

©Alex Majoli/Magnum Photos

NEPAL. Kathmandu. 2006. During political protests in Nepal in 2006, people took to the streets, pushed through into the central old part of Kathmandu, and, at Ason Chowk, they were confronted by police. After 10 years of armed conflict in Nepal, the transition continues to provide many opportunities for women to engage in peacebuilding. UN Security Council resolution 1325 and its subsequent six resolutions recognize the participation of women in peacebuilding processes as key to sustainable peace, economic recovery, social cohesion and political legitimacy.

©Jonas Bendiksen/Magnum Photos

MYANMAR. Yangon. 2014. Myanmar, under the rule of a military junta from 1962 to 2011, has transitioned to a civilian government. Ethnic conflict and rebellion continued but yielded to a draft ceasefire deal in 2015. It is imperative that women should participate in the peace talks to improve the odds of success in reaching an agreement and having a lasting implementation.

©Chris Steele-Perkins/Magnum Photos

UKRAINE. Petrovskyi neighborhood, East Ukraine. 2014. A female mannequin from a destroyed market is used for target practice at a separatist shooting range. During and after conflict, women and girls often experience gender-based violence. Protection measures against sexual violence during armed conflict have been addressed in Resolutions 1325, 1820 and 1888, yet, gender-based violence in conflict continues, perpetuating gender inequalities.

©Larry Towell/Magnum Photos

BRAZIL. Rio de Janeiro. 2010. Members of the elite squad BOPE (the Special Police Operations Battalion of the Military Police) train in the Tavares Bastos favela adjacent to BOPE headquarters, in Laranjeiras. In places experiencing or at risk of conflict, women, men, boys and girls face differentiated security threats that require tailored responses. But these have received little attention in security reform, resulting, for example, in lost opportunities to recruit more women into security forces which can broaden trust and address gender-specific concerns such as sexual violence.

©David Alan Harvey/Magnum Photos

RUSSIAN FEDERATION. Samashki, at the border between Chechnya and Ingushetia. 2000. During conflict between Russian and Chechen forces, Russian woman Vera still lives among the Chechens with her Chechen husband’s relatives. Her grandson plays with a toy gun.

©Thomas Dworzak/Magnum Photos

“Women are essential contributors to the transition from the cult of war to the culture of peace”. — Ambassador Anwarul Chowdhury, High-level Advisory Group of the Global Study on 1325

SYRIA. Semalka Border. 2015. Torin Khairegi, 18, member of a Kurdish group of female soldiers who have taken up the fight against ISIS. The Syrian conflict has grown in intensity for more than two years, leading to millions of displaced and an estimated over 200,000 dead. While some Syrian women have worked to promote peace talks and conflict resolution, the conflict has also seen the participation of women in armed groups, including among Kurdish fighters. Understanding the myriad of roles women play in conflict is essential to address the root causes of conflict and design sustainable disarmament and reintegration programs that respond to their needs.

©Newsha Tavakolian/Magnum Photos

“The evidence shows us unequivocally that women need to be full participants at the peace tables as negotiators and decision-makers in a much more inclusive process. Women have to be able to control where resources are needed; for example, to overcome trauma and the scars of war, or directing practical recovery matters like restitution of property and fields.” — Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, UN Under-Secretary-General and Executive Director of UN Women

TURKEY. Suruc. 2014. Syrian Kurdish refugees enter Turkey from the town of Kobani, Syria and surrounding villages. Conflict in Syria is still raging, contributing to the biggest refugee crisis since World War II. The world is now facing the largest refugee crisis since World War II: at the end of 2014, the number of forcibly displaced persons rose to 59.5 million — one of the highest numbers ever recorded. Women and girls, who represent half of refugees and displaced people, face discrimination and gender-based violence when they are displaced. Protection and humanitarian assistance to refugees and displaced people must integrate gender perspectives and ensure women are also part of the design and implementation of these efforts.

©Michael Christopher Brown/Magnum Photos

“As the men are fighting and trying to make sure that they control power, everything in the household and the community is left in the hands of women. This is very clear when you look at IDP and refugee camps: you don’t find men taking charge of the livelihood of their households.” — Ruth Ojiambo Ochieng, Executive Director, Isis-WICCE, Uganda

VIETNAM.Hanoi. 2004. A woman carries her 52-year-old war veteran husband who lost the use of his legs in 1973. Women in conflict and post-conflict settings continue their roles as caregivers. Conflict leaves them often at the head of a household, taking care of the elderly, the wounded and the children. Recovery programmes need to recognize this population, and be gender-tailored to support women and their family’s well-being.

©Patrick Zachmann /Magnum Photos

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO. Minova. 2014. A veiled survivor testifies while 37 Congolese soldiers facing rape charges are seated behind her. Although more than 1,000 sexual assault victims were identified from the 2012 attacks in Minova, only 47 testified. Special care is taken to provide survivors with disguises, curtains, veils, whatever they may need to feel secure when giving their testimony. The women are referred to by numbers instead of by name to maintain their anonymity.

©Michael Christopher Brown/Magnum Photos

“Sexual violence in conflict needs to be treated as the war crime that it is; it can no longer be treated as an unfortunate collateral damage of war.” — UN Special Representative on Sexual Violence in Conflict, Ms. Zainab Hawa Bangura

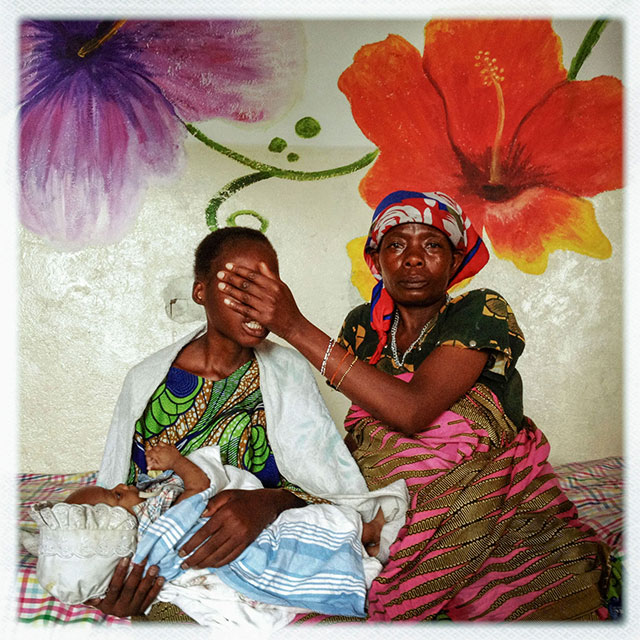

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO. Goma. 2012. A 16-year-old girl from a village near the mining town of Numbi was assaulted by three Hutu militia fighters, one of whom impregnated her. She was at a clinic in Goma with her child and her mother, who is covering her face. As a result of historic Security Council resolutions 1325 and 1820, sexual violence has been recognized as a tactic of warfare, requiring training on sexual violence for peacekeepers and national security forces as well as justice and services for survivors of sexual violence.

©Michael Christopher Brown/Magnum Photos

“Sexual violence is not an issue disconnected from the issue of participation …those affected by or living in fear of sexual violence are less able to participate in political processes and have less access to the justice system. Member States must increase the number of women in the judiciary … as a means of increasing women’s access to justice.” — Sarah Taylor, NGO Working Group on Women, Peace and Security

CAMBODIA. Phnom Penh. 2009. Chea Leang and Robert Petit, co-prosecutors, at the opening of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia. The ECCC is a mixed court set up under a 2003 agreement signed by the UN and the Government that addresses charges of genocide and crimes against humanity committed during the Khmer Rouge regime in the late 1970s. The hybrid tribunal includes the participation of civil parties, female national prosecutors and addresses sexual and gender violence. With the help of UN Women, the ECCC encourages survivors of sexual violence during the Khmer regime to speak out. Including women’s voices and experiences of conflict is essential to peacebuilding and transformative justice. Transformative justice seeks to address not just the consequences of violations committed during conflict but the social relationships that enabled these violations in the first place, and this includes the correction of unequal gendered power relations in society.

©John Vink/Magnum Photos

West Bank. Village of Yanoon. 2002. Palestinian olive harvesters work with the help of Israel-based peace activists Ta’ayush (Arabic for “living together”). Peace between Israel and Palestine remains fragile, despite international mediation efforts. This photo illustrates local efforts involving Israelis and Palestinians working together daily, promoting promoting non-violence and peaceful coexistence.

©Patrick Zachmann/Magnum Photos

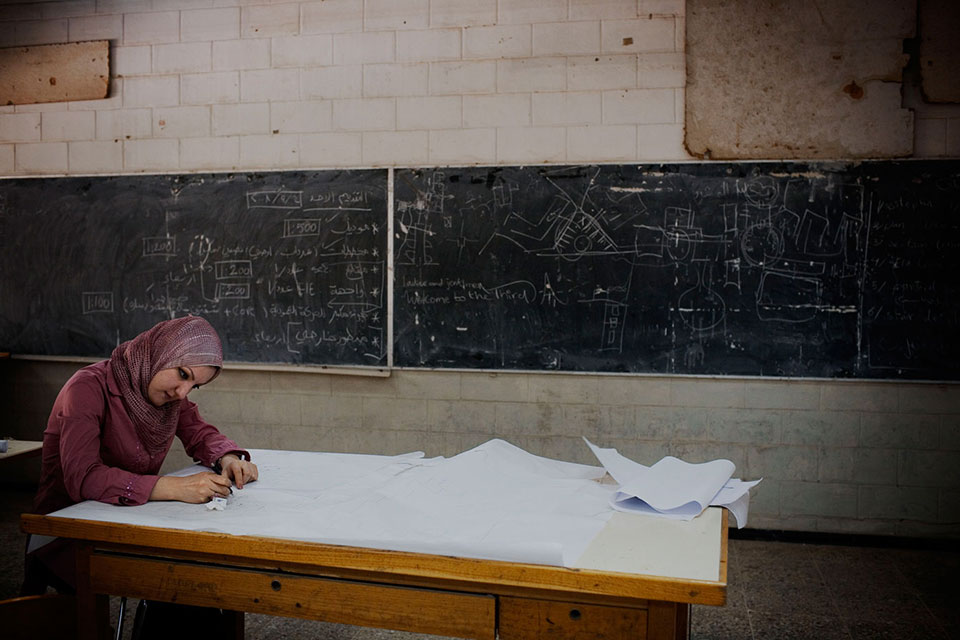

IRAQ. Baghdad. 2008. A woman works at Baghdad’s co-ed College of Engineering. Conflict is a major obstacle to women and girls’ education, and girls’ enrollment in schools often drops in times of war. As noted in the Global Study on 1325, conflict widens the gender gap in school enrollment and retention, and in literacy. Conflict-affected countries typically divert resources away from education, and heightened insecurity keeps girls in particular away from the classroom. When girls’ education is interrupted, they may be forced into early marriage, which also puts them at risk for abuse and sexual violence.

©Jerome Sessini/Magnum Photos

Rwanda. 2014. Kiki Katese lost her family during the genocide in 1994 during which around one million people died. In the aftermath, she was determined to help survivors deal with the trauma. So, she started the first all-women drumming group in Rwanda, where tribal allegiance is left at the door and women stand proudly together. Katese is one example of the vital role played by women in the efforts to build a new society. In Rwanda’s 2003 parliamentary elections women secured 49 per cent of seats in the legislature — the highest number of women parliamentarians anywhere in the world, overtaking Sweden with 45 per cent and way above the world average of 15 per cent. In May 2003, Rwandans ratified a new constitution allotting 30 per cent of decision-making positions to women, a step inspired by the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women.

©Michael Christopher Brown/Magnum Photos

Whether actively confronting security forces in the street or simply going about their daily routine, these photographs ask us: When war is at the door, what does a woman say to her grandson when he plays with a toy gun? While walking home from errands, how does it feel for a woman who must walk through a group of heavily armed police? How much courage does it take for a woman survivor of sexual violence to testify in court, in front of a room full of male soldiers?

The past 15 years have made clear that women are a key resource for promoting peace and stability. Research highlighted in the Global Study on 1325 has established that women’s participation and inclusion makes humanitarian assistance more effective, strengthens the protection efforts of our peacekeepers, contributes to the conclusion and implementation of peace talks and sustainable peace and accelerates economic recovery. For effective interventions and peace that is sustainable it’s critical that women are at the table.

Learn more about UN Women’s work on women, peace and security