COP29 decisions deliver gains for gender equality in climate action, but more remains to be done

The COP29 climate conference concluded on 24 November with several key global agreements on climate action, including a new collective goal for climate-related financing to reach USD 300 billion per year by 2035.

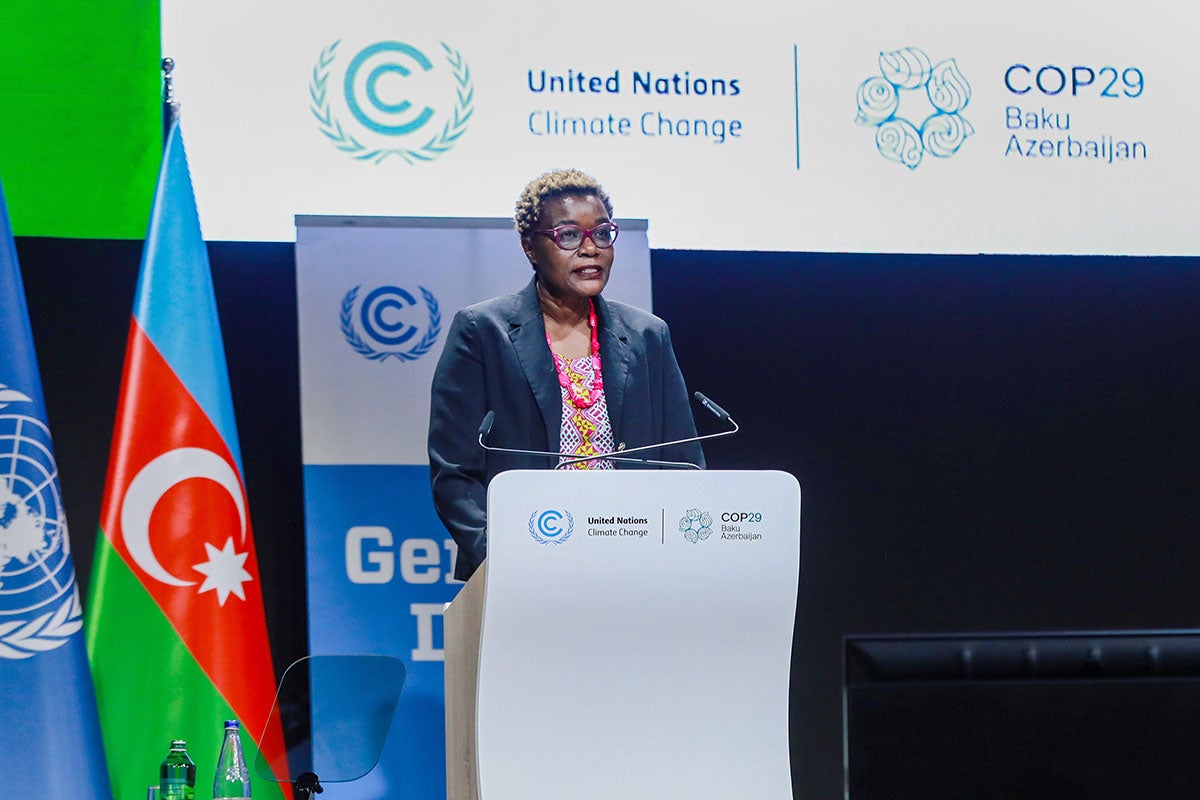

Throughout the conference, supporters of gender equality made their voices heard, calling for a gender-responsive transition to a sustainable global economy, and deepening the integration of gender equality and feminist principles in all climate actions.

Some progress has been achieved in recognizing women as an important beneficiary group of climate finance and on recognizing women in the informal economy as essential to just transitions to low-emission economies. Parties renewed their commitments to gender-responsive climate policy and action, but without the requisite funding and scope to fully address the specific circumstances and intersecting discrimination faced by many women.

Overall, the decisions made at COP29 represent steps forward for gender-responsive climate action, but also reflect some significant missed opportunities.

Steps forward

The positive outcomes of the COP29 negotiations include:

- Extending the Enhanced Lima Work Programme on Gender: The programme’s 10-year extension offers the critical opportunity to further deepen integration of gender equality issues into climate action. The extension is mandated by the Gender and Climate Change Decision, which will advance gender equality and embed gender considerations into the efforts of parties and the processes under the Climate Change Convention. This will help hold governments accountable as they design and implement new policies and plans on climate change, expected to launch in 2025. The call for a new Gender Action Plan in 2025 is an opportunity for parties to raise their ambition and present clear targets and financing goals.

- Acknowledging gender issues in the new climate finance goal: The decision on the New Collective Quantified Goal identifies that climate finance must engage and benefit women and other marginalized groups, and respect, protect, promote, and fulfill human rights.

- Increasing women’s participation: Provisional data shows that 35 per cent of delegates at COP29 were women, compared to 34 per cent in COP28.

Missed opportunities

While the recognition of gender equality in parts of these agreements is welcome, the decisions fell short of the transformational change that those working on gender equality hoped to see in some key areas:

- A lack of clear goals for gender-responsive climate finance: While identifying women among the groups of beneficiaries of climate finance, the USD 300 billion reach financing goal lacks clear-cut commitments to gender-responsive financing in its execution, and lacks measurable targets and enforcement mechanisms. Without clear accountability for gender-responsive approaches to climate financing, the risk of perpetuating existing inequalities remains high.

- Leadership remains largely male: COP29 has shown that gender parity in climate governance structures at national and international levels is still a distant goal, based on the preliminary data available on the gender breakdown of delegations.

- No recognition of intersectionality: Gender equality advocates expected that parties would recognize women “in all their diversity” and how discrimination affects women in different and intersecting ways. While such language was included in early negotiation drafts, it was not present in the texts that were adopted. This lack of recognition of intersectionality limits the ability to address multiple and intersecting forms of discrimination against women and girls in climate action.

- Insufficient gender-disaggregated data: Despite calling for the collection, analysis, and use of gender-disaggregated data after the first Global Stocktake held at COP28 in 2023, a lack of clarity on the necessary mechanisms to do so and insufficient capacity to monitor progress undermines efforts to track the impact of climate change policies on women and girls.

- Failure to adopt the UAE Just Transition Work Programme: A draft text recognized that care work, both paid and unpaid, is increasing due to climate-induced resource scarcity – for instance, fetching water becomes harder in times of drought, floods, and other disasters. Care-related responsibilities are most often undertaken by women and girls, which makes this recognition a significant step forward for integrating women’s concerns into climate policy. However, this text was not adopted, due to a lack of consensus by negotiating parties.

The way forward

As governments, civil society organizations, and multilateral institutions leave Baku, we must continue to build upon the opportunities that COP29 has made possible for gender-responsive climate action. We must recognize that climate change is not gender-neutral, and its solutions will not be either.

A sustainable future demands the full inclusion of women and girls as leaders, decision-makers, and agents of change. UN Women will be working with and supporting parties in the months to come to ensure the adoption of a strong and forward-looking UNFCCC Gender Action Plan at COP30 in Belem, Brazil.