COVID-19 and violence against women: What the data tells us

Before COVID-19, a different pandemic was already threatening the lives and well-being of people around the world: violence against women, impacting at least 1 in 3 women and girls.

From the early days of the COVID lockdowns, women’s organizations noted a significant increase in reported cases of violence against women. But comprehensive data collection on the issue was difficult, because of the sensitivity, stigma and shame around the subject as well as constraints imposed by the pandemic.

Now, a new report from UN Women, which brings together survey data collected in 13 countries across all regions (Kenya, Thailand, Ukraine, Cameroon, Albania, Bangladesh, Colombia, Paraguay, Nigeria, Cote D’Ivoire, Morocco, Jordan, and Kyrgyzstan), confirms the severity of the problem.

Here are five key findings:

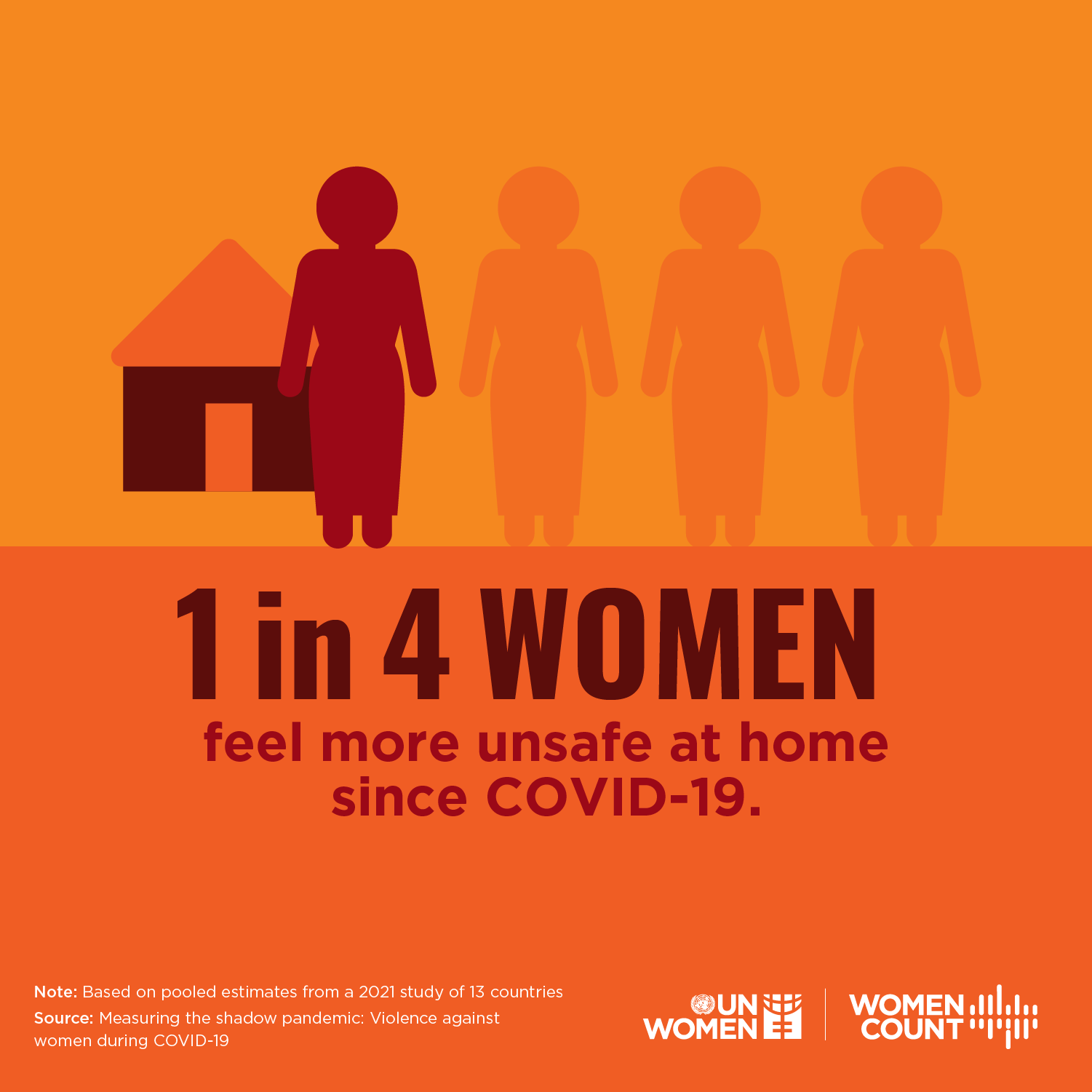

1. The numbers vary across countries and demographics, but overall, the pandemic has increased women’s experiences of violence and eroded their feelings of safety.

Across the 13 countries surveyed, 2 in 3 women report that they or a woman they know has experienced violence at some point in their lifetime. Nearly 1 in 2 report direct or indirect experiences of violence since the start of the pandemic.

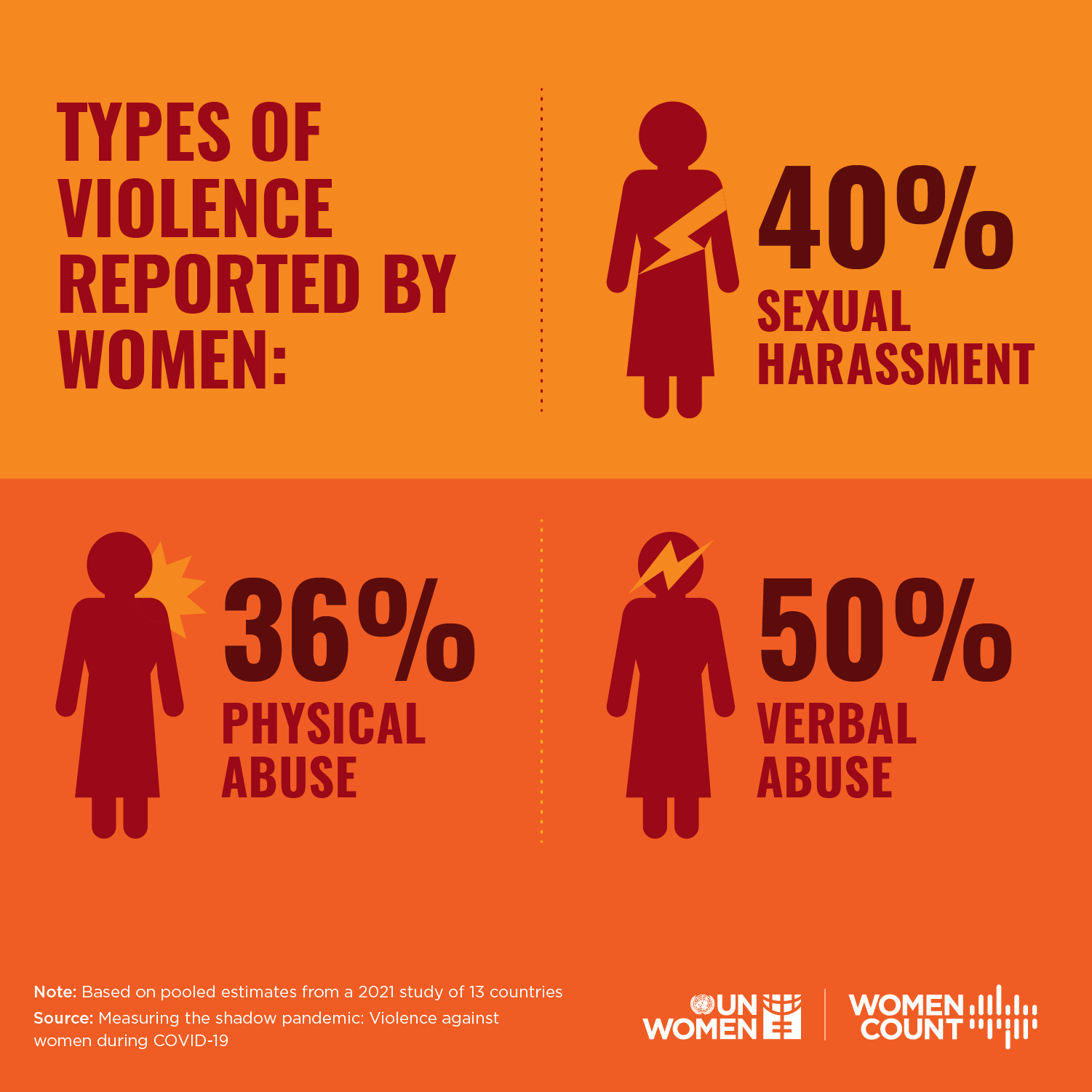

The most common form is verbal abuse (50%), followed by sexual harassment (40%), physical abuse (36%), denial of basic needs (35%) and denial of means of communication (30%). Seven in 10 women surveyed believe violence against women is common in their community.

Most women believe that COVID has made things worse. Nearly 7 in 10 women think domestic violence has increased during the pandemic, and 3 in 5 think sexual harassment in public has increased. In many cases, heightened demand for shelters and other forms of support has remained unmet due to operational constraints.

For Romela Islam, the abuse by her husband began long before COVID-19. But it was not until December 2020 that she and her 4-year-old daughter were able to escape. Islam found refuge at a women’s shelter, and the two have begun to build a new life. Reduced shelter capacity, however, means many women have not had this same chance.

Other people always told me how to dress, where to go, and how to live my life. Now, I know these choices rest in my hands. — Romela Islam

2. Violence against women has had a significant impact on women’s mental health during the pandemic.

It’s hard to overstate the psychological toll of COVID-19. It has isolated us, upended our lives and made us afraid for our physical well-being. For women simultaneously exposed to violence, the compounded emotional impacts are that much worse.

Women who report feeling unsafe at home or in public, or who report direct or indirect experiences of violence, are more likely to say that COVID has worsened their feelings of stress and anxiety, particularly in cases of physical violence. These women are also more likely to report an inability to stop worrying and a lack of interest in doing things.

3. Socioeconomic factors play a major role in women’s experiences of violence.

Economic stressors are a known driver of violence against women, a trend that has clearly held during COVID-19. Among women whose partner has no earnings, 4 in 5 report that they or a woman they know has experienced at least one form of violence. Food insecurity is also a factor: women who say domestic violence is very common are more likely to be food insecure than those who say it is uncommon, as are women who have experienced or know someone who has experienced violence when compared to those who have not.

Women’s economic roles within their household also have an impact. Full-time unpaid caregivers are more likely to report they or a woman they know has experienced violence, as compared to employed women, unemployed women and students. On the flip side, earning an income appears to reduce experiences of violence: women with an income are less likely to perceive violence against women as a problem and domestic violence as common. The exception: women who out earn their partner perceive domestic violence as more common and feel less safe at home than those who don’t.

4. Age is no barrier when it comes to violence against women.

While many surveys on violence against women focus specifically on women of reproductive age (15-49), this survey sought responses from all women 18+. The findings reveal that age doesn’t offer much protection: women over 60 experience violence at similar rates to younger women, with over half reporting that they or a woman they know has experienced some form of violence.

5. Especially in domestic violence situations, women often do not seek outside help.

When asked who they thought women experiencing domestic violence would seek help from, 49% of respondents said women would seek help from their family, while only 11% said women would seek help from police, and 10% said they would go to support centres (shelters, women’s centres, etc.).

For those who do seek outside help, it can often be a crucial turning point. Goretti Ondola, a Kenyan woman whose husband died in 2001, has suffered severe abuse from her husband’s family ever since. In late 2020, after they beat her to the point of hospitalization, she reached out to a local human rights defender. By initiating an alternative dispute-resolution process while also pushing the case to court, the human rights defender helped secure a settlement that granted Ondola her own property and land title. “It is like beginning a new life after 20 years,” she says.

Despite its persistent prevalence, violence against women is preventable. Here are 5 recommendations for action from UN Women experts:

1. Put women at the centre of policy change, solutions and recovery.

Women’s equal representation in COVID-19 task forces is key to making sure that their voices, needs and rights are brought into pandemic response and recovery plans. Globally, women make up less than a quarter (24%) of COVID-19 task force members. Countries can address this gap by including women’s organizations in recovery planning and longer-term solutions to violence against women and girls.

2. Provide resources to address violence against women in COVID-19 recovery and response plans.

COVID recovery and response plans should include evidence-based measures to address violence against women and girls. Such measures must be holistic, multisectoral and fully integrated in national and local policies.

3. Strengthen services for women who experience violence, including where COVID-19 has increased existing risk factors and vulnerabilities.

Efforts put in place during the pandemic to strengthen services, including shelters, hotlines and reporting mechanisms, psychosocial support, and police and justice responses to address impunity, must be maintained. National and local governments must bridge the gaps in these services so that all women and girls are able to access them.

4. Invest in medium and long-term prevention efforts to end violence against women and girls.

Prevention efforts should address gender norms, root causes and risk factors of violence against women. Prevention initiatives can include dedicated curricula in education systems, economic support for women and households, and awareness and messaging campaigns to influence and change social norms through media.

5. Collect sex-disaggregated data on the impact of COVID-19.

For better policies, we need adequate data. This must include sex and age disaggregated data on mid- and long-term impacts on violence against women and girls. Face-to-face household surveys should be resumed when possible, and administrative data systems should be strengthened to better assess the needs and capacity of response services.