New report shows how feminism can be a powerful tool to fight climate change

By 2050, climate change may push up to 158 million more women and girls into poverty and see 236 million more face food insecurity. The climate crisis fuels increases in conflict and migration, as well as exclusionary, anti-rights political rhetoric targeting women, refugees, and other vulnerable groups.

Those dire trends—and ways to reverse them—are charted in a new report by UN Women titled “Feminist climate justice: A framework for action”.

The report shows how crises around the world, ranging from economic inequality to geopolitical gridlock, are amplified by climate change and have disproportionate impacts on women and girls. It calls for a clear vision of feminist climate justice that integrates women’s rights into the global fight against environmental catastrophe.

The vision for feminist climate justice is a world in which everyone can enjoy the full range of human rights, free from discrimination, and flourish on a planet that is healthy and sustainable. The report breaks down that vision into the four Rs:

Recognizing women's rights, labour, and knowledge

Policies must recognize that women can offer unique knowledge and expertise—including among indigenous, rural, and young populations—that can be used to support effective climate action.

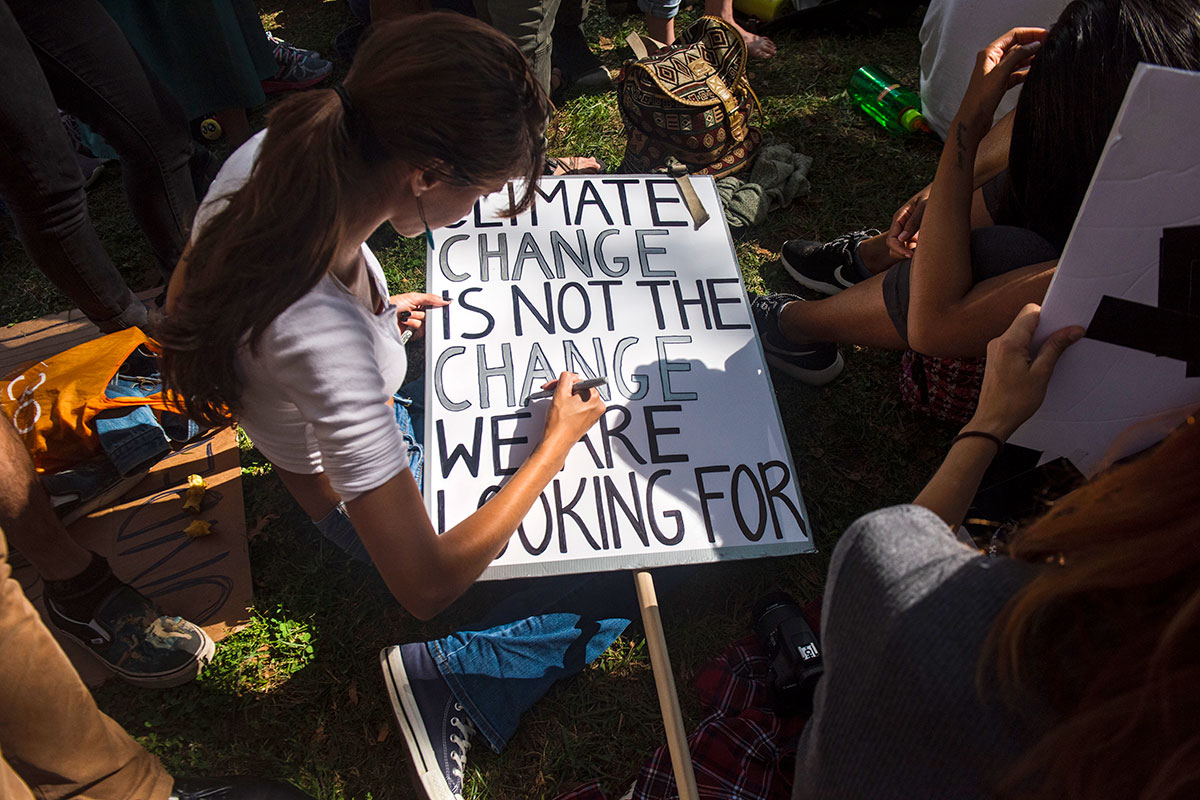

Women and girls around the world have been at the forefront of climate activism and have used a variety of methods to protect the environment and push back against damaging extraction projects. Women farmers have also formed cooperatives and groups to share their workloads and increase their productivity and income.

Policies should build on these successes while also recognizing that women shoulder disproportionate care responsibilities, have fewer economic resources than men, and have lower levels of literacy and access to technology. These inequalities are exacerbated by climate change.

The existing burden of unpaid family care is worsened when food prices climb due to poor harvests, or when family members’ healthcare needs increase amid rising temperatures. Girls are more likely to drop out of school in areas prone to drought. Governments must ensure that women’s and girls’ needs and rights are integrated into policies on disaster response, gender-based violence, food production, economics, social discrimination, and other topics that intersect with the climate crisis.

Redistributing economic resources

Reversing climate change will require moving resources away from extractive and environmentally damaging activities, and towards those that prioritize care for people and the planet, the report says.

Policies must ensure that a transition to a green economy aides women’s access to employment opportunities, land, education, and technology. Publicly financed social protection systems should support women and girls’ economic and social well-being and their resilience as the climate changes.

For example, school-based food programmes are not only able to alleviate some of women’s unpaid care work by supplying children with nutritious food, but can further support feminist climate policy by sourcing meals from small-scale, environmentally friendly women farmers.

Representing women's voices and agency

Women human rights defenders, feminist groups, and others pushing for a gender-responsive approach to climate change must be integrated into environmental policymaking at all levels.

At present, women are underrepresented in environmental protection ministries at the national level. While women’s participation in national delegations to the UN COP climate conferences rose from 30 to 35 per cent from 2012 to 2022, the proportion of delegations headed by women declined slightly from 21 to 20 per cent over the same period.

One promising example given in the report is La Via Campesina, a global organisation representing some 200 million farmers, rural labourers, and peasants. Women and people with diverse gender identities have established a Women’s Assembly within the organization that works to ensure gender parity, integrates a gender-based approach to the group’s demands, and empowers them in decision-making on food systems and climate at every level, from local communities to the UN System.

Repairing inequalities and historical injustices

Financial commitments to fight climate change must focus on the people and countries most at risk. Responding to the climate crisis will require addressing existing inequalities and historical injustices.

One example is the issue of climate debt: the fact that, since 1850, countries in the global north have been responsible for 92 per cent of the world’s excess emissions. To address that imbalance, the report calls on wealthy countries to meet their commitments to finance climate programmes and ensure that funds go to the most vulnerable countries and grassroots women’s organisations.

While a loss and damage fund was agreed upon at the COP conference in 2022, contributions are voluntary and no mechanism has been established to hold wealthy countries to account for historical environmental damage and its consequences, such as the loss of land, housing, and crops because of extreme weather events.

However, financial reparations are only one part of the programme: wealthy countries also need to find responses for the non-economic consequences of climate change, such as increased levels of gender-based violence and unpaid care work, and peoples’ displacement from their ancestral lands resulting in a loss of cultural heritage and knowledge.

What comes next

The COP28 climate conference, which inaugurates the Global Stocktake, is a crucial milestone to make countries accountable for their climate action.

At that conference, as well as at all other spaces where climate policies are discussed and implemented, leaders and policymakers must ensure that their responses to environmental challenges also integrate the needs and rights of the world’s women and girls.

Working with partners, UN Women plans to develop a new tool, the gender equality and climate policy scorecard, to monitor gender-responsive national climate policies systematically, which will create a strong foundation for future gender-inclusive climate policy.

The recommendations in the Feminist Climate Justice report are just first steps towards global climate responses that incorporate gender-responsive policies. It is essential that feminist goals continue to be integrated into the world’s response to the climate crisis.