Zimbabweans say yes to new Constitution strong on gender equality and women's rights

Date:

“As a woman of Zimbabwe, I personally wanted a Constitution that is fit for me,” said Zimbabwe’s Deputy Minister of Women Affairs, Gender and Community Development and Member of Parliament, Jessie Majome, who participated in Zimbabwe’s Constitution-making process as part of the Select Committee of Parliament that facilitated the process.

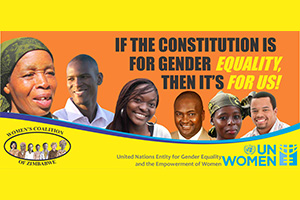

Photo Credit: Women’s Coalition of Zimbabwe

In an overwhelming endorsement, 95 per cent of Zimbabweans (3,079,966) voted yes to a draft Constitution in a referendum on 16 March – a vote 10 years in the making. As the results were announced, congratulations messages circulated through telephone calls, e-mails, and SMS exchanges among Zimbabwean women, who were actively involved. Since Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980, women have lobbied arduously to be treated as equal citizens with equal entitlements before the law.

The successful approval of the draft Constitution represents an inherent victory for them, with positive provisions for women in several areas. The ‘Yes’ vote will herald a new Supreme Law, to be enacted by Parliament after it reconvenes on 7 May, which will mandate gender equality and protect women’s rights.

The new Constitution will also be more aligned with several of the key international and regional gender equality and women’s rights instruments that Zimbabwe has signed and ratified. These include the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa – and the Southern African Development Community Gender and Development Protocol – among others.

The draft Constitution approved by referendum opens with provisions stating that respect for gender equality is one of the country’s Founding Values. The Declaration of Rights includes a section on women’s rights, has been expanded to include socioeconomic and cultural rights, and it could be used in legal or judicial proceedings. This means new opportunities for women in jobs, education, finance and credit must be ensured by the government and in national funding.

The new Constitution also includes a special measure to increase women’s representation in Parliament, introducing for this purpose in the National Assembly, 60 reserved seats for women who will be elected through a system of Proportional Representation based on the votes cast for political party candidates in a general election for the 210 members. The 60 reserved seats for women will be additional to any women elected to the other 210 seats. This measure will be in effect for the first two Parliaments after the Constitutional enactment is published in the official Gazette. It is still unclear whether the new measures will apply to the upcoming elections, dependent on whether the enactment happens before then.

The provisions will also apply to the Senate, to the 60 directly elected members among a total of 80 (the other 20 are reserved for tribal Chiefs and people with disabilities). The new constitutional measure states that the 60 elected Senators will be chosen from a party-list system of Proportional Representation, in which male and female candidates are listed alternately, with every list headed by a female candidate.

The new Constitution will also establish a Gender Commission tasked with promoting gender equality in all spheres of life. Its mandate will include: the investigation of possible gender rights violations, receiving and considering gender-based complaints from the public, conducting research on gender and social justice issues, recommending changes to discriminatory laws and practices, and proposing affirmative action programmes.

As all existing laws will be reviewed to ensure they comply, the new Constitution is expected to have a domino effect. Additional laws will also be drafted where gaps currently exist.

A history of Constitution-building

“[Women] dropped the ball in the last process and had to wait for almost 10 years before getting a chance again” to work on a Constitution to improve the situation for women, said Perpetua Bwanya, who was active in the National Constitution Assembly-led process in 1999-2000. Fast forward to 2012, when it came to choosing between the ‘politics of boycott’ and the ‘politics of engagement’, women, she said, chose this time to engage and the choice paid off.

During the first Constitution-making process in 1999-2000, women active in advocacy and lobbying formed alliances and coalitions with broader civil society movements of the time.

The result was a women’s movement rallying for a ‘No’ vote in that referendum, because it was a government-led process that they did not feel was participatory or transparent. Women activists interviewed now admit that “they mobilized a dissenting vote against the process at the time, without paying attention to the contents of the draft Constitution that went to Referendum,” which also had strong gender equality and women’s rights provisions.

During the second Constitution-making process (2009-2013), Zimbabwean women left nothing to chance. This time around, women stayed singularly focused on women’s needs, rights and concerns when lobbying for constitutional provisions and principles and decided not to be swayed by politics or political divisions.

With technical and financial support from UN Women and UNDP, women activists, senior politicians, women parliamentarians and academics formed what they dubbed the Group of 20 (G-20), a gender equality and women’s rights constitutional lobby group. This group strategized, drafted constitutional provisions, lobbied the constitutional drafters, and honed their lobbying and advocacy skills to become a key information source on gender equality, women’s rights and the Constitution.

When the Draft Constitution was first released in July 2012, 28-year-old Rudo Chigudu recalls that it seemed like a huge and very technical document that people said would be hard to understand.

“But through [UN Women’s Gender Forum]dialogues on gender and how it is reflected in the Draft Constitution, the massive document became accessible to me,” said Chigudu, who is one of the coordinators of Katswe Sistahood, an organization working with young women on sexual and reproductive health rights. “I realized how the day-to-day lives of women relate to the Constitution and the rights spelled out there; from feeding children, having access to quality health care, shelter, education — all of these issues are in the Constitution.”

Related links:

A new coalition takes the lead on women’s constitutional rights in Zimbabwe