COVID-19 and its economic toll on women: The story behind the numbers

Date:

The impacts of crises are never gender-neutral, and COVID-19 is no exception.

Economic crises hit women harder. Here’s why:

- Women tend to earn less.

- Women have fewer savings.

- Women are disproportionately more in the informal economy.

- Women have less access to social protections.

- Women are more likely to be burdened with unpaid care and domestic work, and therefore have to drop out of the labour force

- Women make up the majority of single-parent households.

For the single mother in South Sudan, COVID-19 lockdown measures have paused her small business that brings food to the table.

For the domestic worker in Guatemala, the pandemic has meant no job and no unemployment benefits or other protection.

For countless women in economies of every size, along with losing income, unpaid care and domestic work burden has exploded.

While everyone is facing unprecedented challenges, women are bearing the brunt of the economic and social fallout of COVID-19.

Women who are poor and marginalized face an even higher risk of COVID-19 transmission and fatalities, loss of livelihood, and increased violence. Globally, 70 per cent of health workers and first responders are women, and yet, they are not at par with their male counterparts. At 28 per cent, the gender pay gap in the health sector is higher than the overall gender pay gap (16 per cent).

Here’s how COVID-19 is rolling back on women’s economic gains of past decades, unless we act now, and act deliberately.

The future of the poverty gender gap

“For the last 22 years, extreme poverty globally had been declining. Then came COVID-19, and with it, massive job losses, shrinking of economies and loss of livelihoods, particularly for women. Weakened social protection systems have left many of the poorest in society unprotected, with no safeguards to weather the storm,” says Ginette Azcona, lead author of UN Women’s latest report From Insights to Action and UN Women’s Senior Research and Data Specialist.

The recently released report shows that the pandemic will push 96 million people into extreme poverty by 2021, 47 million of whom are women and girls. This will bring the total number of women and girls living on USD 1.90 or less, to 435 million.

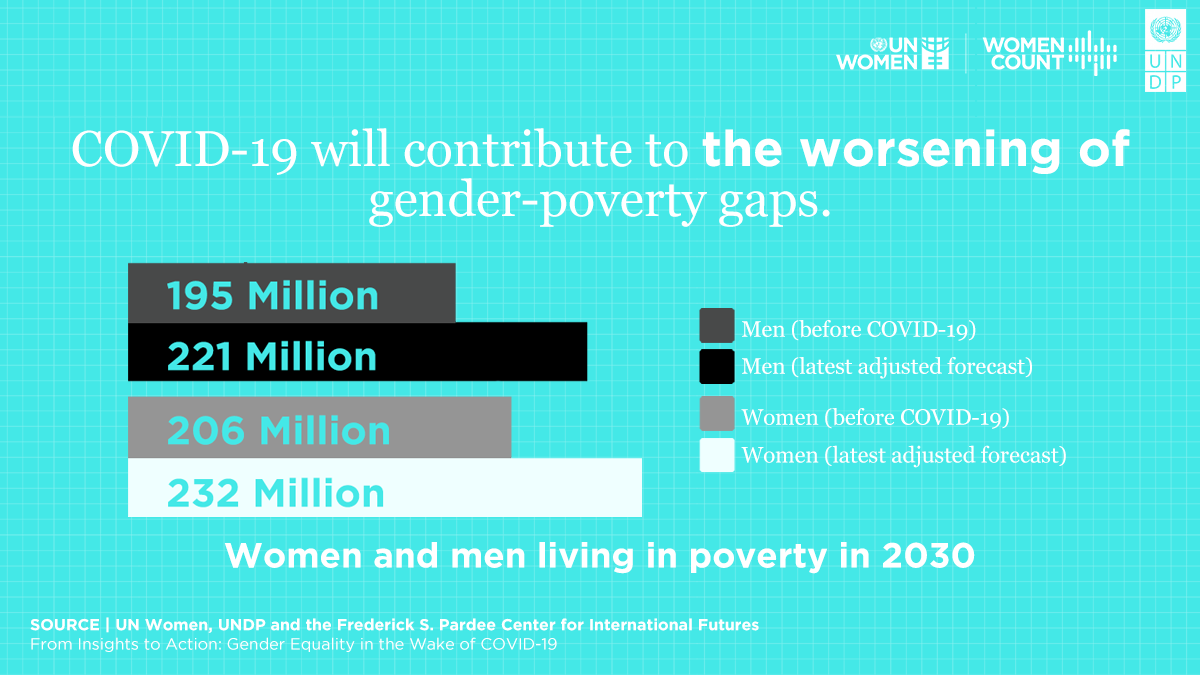

The pandemic-induced poverty surge will also widen the gender poverty gap – meaning, more women will be pushed into extreme poverty than men. This is especially the case among those aged 25 to 34, at the height of their productive and family formation period. In 2021, it is expected there will be 118 women aged 25 to 34 in extreme poverty for every 100 men aged 25 to 34 in extreme poverty globally, and this ratio could rise to 121 poor women for every 100 poor men by 2030.

The resurgence of extreme poverty as a result of the pandemic has revealed women’s precarious economic security,” adds Antra Bhatt, Statistics Specialist and co-author of the report From Insights to Action. “Women typically earn less and hold less secure jobs than men. With plummeting economic activity, women are particularly vulnerable to layoffs and loss of livelihoods.”

Women’s paid labour and women-run businesses will be hit hard(est)

Women are losing their jobs. The pandemic and measures to prevent its spread are driving a disproportionate increase in women’s unemployment (as compared to men) and also decreasing their overall working time.

In South Sudan, Margaret Raman, a single mother of five who sells beans and groundnuts at a local market, lost more than 50 per cent of her income as social distancing guidelines drastically reduced the number of people visiting the market.

“Our businesses have been growing, only to be disrupted by COVID-19,” she said. “Since COVID-19, our lives have not been the same. Under normal circumstances, I make about SSP 28,000 [USD 100] in a week. This has recently been reduced to below half, SSP 10,000 [USD 34] a week.”

Raman’s story is playing out in other parts of the world too. Since the start of the pandemic, in Europe and Central Asia, 25 per cent of self-employed women have lost their jobs, compared to 21 per cent of men –– a trend that is expected to continue as unemployment rises. Projections from the International Labour Organization suggest the equivalent of 140 million full-time jobs may be lost due to COVID-19; and women’s employment is 19 per cent more at risk than men.

These women are the faces behind the headlines, the people most affected by the economic impact of COVID-19 Unless, policies intentionally enable economic relief measures and deliberately target women, support women-led businesses and their income security, their situation will only worsen.

The most impacted industries have more women

Women are overrepresented in many of the industries hardest hit by COVID-19, such as food service, retail and entertainment. For example, 40 per cent of all employed women – 510 million women globally – work in hard-hit sectors, compared to 36.6 per cent of employed men.

“The financial impact on hospitality alone has just been so staggering,” said Ryancia Henry, a 32-year-old Caribbean national working in the hospitality industry in the United States of America. “I worry for myself depending on how long this goes on, what kind of decisions do I have to make, to be financially okay, and I have the same concerns for my team. I send some funds home, to help my mom. I worry about maintaining some payments.”

Within some of these sectors where informal employment is common, workers were already subject to low pay, poor working conditions and lacking social protection ( pension, healthcare, unemployment insurance) before the pandemic.

Globally, 58 per cent of employed women work in informal employment, and estimates suggest that during the first month of the pandemic, informal workers globally lost an average of 60 per cent of their income.

When everyone stayed home, they sent the domestic workers packing

For domestic workers, 80 per cent of whom are women, the situation has been dire: around the world, a staggering 72 per cent of domestic workers have lost their jobs. Even before the pandemic, paid domestic work, like many other informal economy jobs, lacked basic worker protections like paid leave, notice period or severance pay.

When the COVID-19 crisis came to Timor-Leste, Ana Paula Soares, a 27-year-old who has been her family’s breadwinner since 2017, lost her income and was left with no way to support her family.

Her story is the same as millions of women workers in the informal economy.

“It’s hard to make money at this time. People who work at the office, they continue to work from home and earn their salary regularly; but domestic workers cannot. Domestic workers should also be entitled to a salary during times of crisis,” said Soares. “Some didn’t even receive their salary when they were asked to stop in the middle of the month. I wish all employers would treat their employees equally.”

In the absence of help from employers, domestic workers in Latin America have been organizing their own networks of assistance. Workers associations and unions are playing a critical role: “Their response has been truly admirable,” said Adriana Paz, coordinator for Latin America at the International Domestic Workers Federation. “They have raised funds, door to door, at the local level and with political authorities. They have organized community kitchens [and] have brought food to their affiliates’ plates.”

“Domestic workers’ associations and unions are among the few organizations that have brought relief to the poorest neighbourhoods,” added Paz.

Inequality at home and unpaid care

As quarantine measures keep people at home, close schools and day-care facilities, the burden of unpaid care and domestic work has exploded. Both for women and men. But even before COVID-19, women spent an average of 4.1 hours per day performing unpaid work, while men spent 1.7 hours – that means women did three times more unpaid care work than men, worldwide. Both men and women report an increase in unpaid work since the start of the pandemic, but women are continuing to shoulder the bulk of that work.

School and daycare closures, along with the reduced availability of outside help, have led to months of additional work for women. For working mothers, this has meant balancing full-time employment with childcare and schooling responsibilities.

The responsibility of caring for sick and elderly family members often falls on women as well.

In Serbia, a call-in counselling centre run by the non-profit organization Amity, offers support to those who are lonely or overwhelmed with care and housework during the lockdown.

“Most of the calls we get are from either older or younger women who care for their older relatives and family members, who found themselves in an endless cycle of cooking, cleaning and care at home during the lockdown,” said Nada Sataric, founder of Amity. “Now is the time to acknowledge this unpaid care work and redistribute this burden.”

Poverty and gaps in basic services and infrastructure add to women’s unpaid workload. Globally, around 4 billion people lack access to safely managed sanitation facilities, and roughly 3 billion lack clean water and soap at home. In these situations, women and girls are the ones tasked with water collection and other tasks necessary for day-to-day survival.

The consequences will outlast the pandemic

- In general, increased unemployment tends to encourage people to go back to traditional gender roles: unemployed men are favored more heavily in the hiring process when jobs are scarce, while unemployed women take on more household and care work.

- During the 2008 economic crisis, the diversion of government funds toward relief efforts culminated in major cuts to social services and benefits, with heavy impacts on women.

- During the recent Ebola outbreak, quarantines significantly reduced women’s economic activity, driving a spike in poverty and food insecurity. While men’s economic activity rebounded quickly, women’s did not.

Economic insecurity is not just jobs, and income loss today. It has a snowball effect on the lives of women and girls for years to come. Impacts on education and employment have long lasting consequences that, if unaddressed, will reverse hard-won gains in gender equality.

Estimates show that an additional 11 million girls may leave school by the end of the COVID crisis; evidence from previous crises suggests that many will not return.

A widening education gender gap has serious implications for women, including a significant reduction in what they earn and how, l and an increase in teen pregnancy and child marriage.

Lack of education and economic insecurity also increase the risk of gender-based violence. Without sufficient economic resources, women are unable to escape abusive partners and face a greater threat of sexual exploitation and trafficking.

These consequences won’t disappear when the pandemic subsides: women are likely to experience long-term setbacks in work force participation and income. Impacts on pensions and savings will have implications for women’s economic security far down the road.

The fallout will be most severe for the most vulnerable women among us, those who are rarely in the headlines: migrant workers, refugees, marginalized racial and ethnic groups, single-parent households, youth and the world’s poorest. Those who have recently escaped extreme poverty will likely fall back into it.

Recovery efforts must reach women

“Despite the clear gendered implications of crises, response and recovery efforts tend to ignore the needs of women and girls until it’s too late. We need to do better,” urges UN Women’s Chief Statistician, Papa Seck. “But most countries are either not collecting or not making available data broken down by sex, age and other characteristics – such as class, race, location, disability and migrant status. These acute data gaps make it extremely difficult to predict the pandemic’s full impact in countries and communities. They also raise the concern that COVID-19 policy response will ignore the priorities of the most vulnerable women and girls.”

Here are five steps that governments and businesses can take to mitigate the negative economic impacts of COVID-19 on women.

- Direct income support to women

Introduce economic support packages, including direct cash-transfers, expanded unemployment benefits, tax breaks, and expanded family and child benefits for vulnerable women and their families. Direct cash-transfers, which would mean giving cash directly to women who are poor or lack income, --can be a lifeline for those struggling to afford day-to-day necessities during this pandemic. These measures provide tangible help that women need right now. - Support for women-owned and -led businesses

Businesses owned and led by women should receive specific grants and stimulus funding, as well as subsidized and state-backed loans. Tax burdens should be eased and where possible, governments should source food, personal protection equipment, and other essential supplies from women-led businesses. Economic relief should similarly target sectors and industries where women are a large proportion of workers. - Support for women workers

Implement gender-responsive social protection systems to support income security for women. For instance, expanded access to affordable and quality childcare services will enable more women to be in the labour force. Bridging the gender pay gap is urgent, and it begins by enacting laws and policies that guarantee equal pay for work of equal value and stop undervaluing the work done by women. - Support for informal workers

Provide social protection and benefits to informal workers. For informal workers left unemployed, cash transfers or unemployment compensation can help ease the financial burden, as can deferring or exempting taxes and social security payments for workers in the informal sector. - Reconciliation of paid and unpaid work

Provide all primary caregivers with paid leave and reduced or flexible working arrangements. Provide essential workers with childcare services. Unprecedented measures to address the economic fallout have already been taken, but comparatively few measures have been directed at supporting families grappling with paid and unpaid work, including care needs. More efforts are also needed to engage citizens and workers in public campaigns that promote equitable distribution of care and domestic work between men and women.